Soon silence returned to the disc business. It was a union-busting loophole that Petrillo naively walked into, and - upon closer consideration - quickly walked back with threats of secondary strikes. If you’ve studied popular music, maybe you’ve noticed that sudden cluster of a cappella recordings in 1943 and wondered, was it passing musical fad or an expression of wartime sentiment? It was neither. Suddenly, Sinatra, Perry Como and Dick Haymes began recording with their own choral accompaniments. Not only was the song a hit, it was a precedent. On July 2, Crosby made “Sunday, Monday Or Always” with the Ken Darby singers. Decca president Jack Kapp cautiously asked Petrillo if an a cappella choir would violate the strike. So, in the middle of the strike, Decca scheduled its first musician-less Crosby session. By 1943 he was the only entertainer to dominate all three media platforms simultaneously: broadcasting, records and movies. He didn’t have the standing yet to challenge the great Petrillo.īut Bing Crosby did. Sinatra had just left Tommy Dorsey and was still looking for a record company. He denied it, but the idea was in the air. 15, 1942, DownBeat quietly whispered a rumor on page 15 that Sinatra was considering recording with an a cappella chorus. If singers could not record with musicians, maybe they could record with other singers. And Petrillo excused Victory Discs from any sanction, since they were strictly for the armed forces. The strike affected only commercial records, not radio, clubs or concerts.

People may change, but a recording is immutable. It was rushed back into print in 1943 for a much younger audience who barely remembered Vallee as a singer and now thought of him as a character actor in Preston Sturgis films. The only available version was the 1931 original by Rudy Vallee on Victor. But neither Wilson nor any other singer could re-record it.

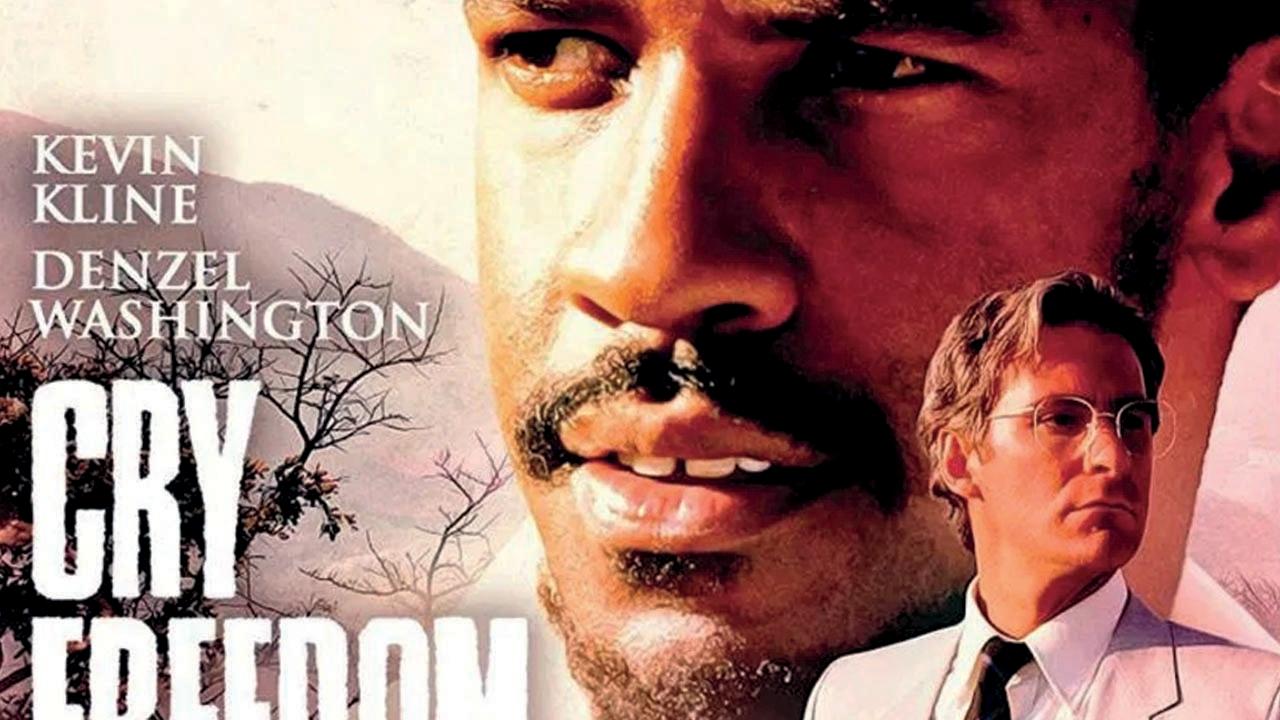

#KEN DARBY SINGERS THE BATTLE CRY OF FREEDOM MOVIE#

The movie turned it into a wartime romantic anthem. catalog when the studio blew off the dust and inserted it into Casablanca for Dooley Wilson. “As Time Goes By” was a forgotten 1931 song in the Warner Bros. Hollywood generated hits, too, not all of them expected. Among the songs was “All Or Nothing At All.” When Columbia reissued it in 1943 as a Frank Sinatra disc, the same record that had sold less than 8,000 four year earlier became Sinatra’s first million seller. When Sinatra-mania swept the country in 1942–’43, publisher Lou Levy reminded Columbia that it had recorded the singer as an unknown “boy vocalist” with Harry James in 1939. Since new songs couldn’t get recorded, reissues boomed, giving old ones a second chance. But the pile was low by then because no matter how carefully the companies rationed their stashes, no one could record a song in July 1942 that hadn’t been written yet. The following spring it hatched into a huge hit. Harry James recorded “I’ve Heard That Song Before” just under the line on July 31. Meanwhile, that backlog would have a shelf life of only about six months. Not even a personal request from President Roosevelt moved him. But Petrillo’s stubbornness was surpassed only by his patience. Had it been brief, it would have left no mark. At midnight, July 31, 1942, the race ended and the standoff began. Like officious squirrels fixing for a cold winter, they banked backlogs of inventory in marathon sessions.

During May, June and July, the rush was on. There were three major companies then: Victor, Columbia and Decca. When he demanded record companies pay into a union fund for musicians whose records were broadcast, they drew the line and prepared for battle. But once elected AFM chief in 1940, Petrillo’s power became national and dangerous. In 1937, as president of Local 10 in Chicago, he had briefly shut down the city’s studios. The joke was always the same: Nobody messes with the almighty godfather of 130,000 working musicians.įor years, Petrillo’s luddite views of the record business had convinced him that discs stole up to 60% of live music jobs. To comics from Bob Hope to Bugs Bunny, he was a punchline. But in the 1940s and ’50s, Petrillo was the most famous labor leader in America. Today, I’d wager not a single reader of this story could name the current president of the AFM. But that was to underestimate the imperial rule of James C. Everyone figured it would be brief once folks came to their senses. Unlike the other war - Germany and Japan - this was a fight between the American Federation of Musicians and the record industry. The New York Times ran it as a front-page, above-the-fold war story. Like the DownBeat banner said, “All Recording Stops Today.” Then, 80 years ago this August, Jimmy Petrillo lowered the boom on the record business. The writing had been on the wall for weeks, maybe years. 1, 1942, issue of DownBeat announces the recording ban.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)